The Alchemy of Horror: Darkness as Doorway

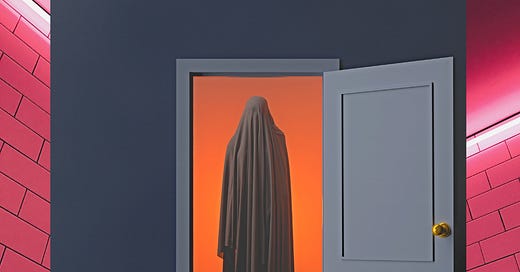

Horror is more than just fright. It is a form of initiation. Whether through nightmares, trauma, or fiction, horror breaks the surface of the self and exposes what lies beneath. It’s often monstrous, yet always sacred. It is the sacred language of the psyche when normal means of communication with the self have failed.

The work of Carl Jung took my life as a searching adolescent by storm. His writings on the shadow exposed the nature of horror, the dark counterpart of the conscious self. As a psychotherapist and writer, I realized that the monster in a dream or story is not just a threat; it is the missing piece of the soul. Jung taught that a person does not reach enlightenment by imagining figures of light but by making darkness conscious. Horror’s monsters, whether in the literary or psychic realms, are invitations to descend into the underworld—into the unconscious—where transformation begins.

Stephen King’s Doctor Sleep depicts this descent. The adult Danny Torrance, still marked by the Overlook Hotel, faces a lifetime of addiction and psychic suffering. His journey to healing isn’t through denial but through confrontation with trauma, with ghosts, and with the psychic burden of his “shining.” The horror isn’t just outside him; it’s internalized, embedded in memory, addiction, and shame. Yet, through this, a redemptive hope appears. Horror, in this context, becomes a route toward psychic integration.

In the world of Simon R. Green’s Angels of Light and Darkness, horror wears a mythic mask. Monsters and demons stalk the Nightside. It’s a hidden underworld pulsing with archetypal intensity. But beneath the noir violence lies a depth psychological insight: every angel casts a shadow, and even the darkest entities hold keys to deeper truth. The protagonist, like a dreamer or trauma survivor, must engage with the terrifying forces rather than destroy them. In doing so, the Nightside itself becomes an alchemical crucible where good and evil, self and other, mingle and transform.

Michael Eigen, the mystic psychoanalyst, echoes this perspective. In The Psychotic Core, he states that pain is essential to psychic healing. He asserts that there is no creation without wounding or bleeding. Therefore, horror transforms from pathology to a sacred fire. His patients’ accounts of psychic invasions, demonic presences, or overwhelming dread are not dismissed as symptoms. Instead, they are regarded as profound psychic truths, fragments of the real, burning their way into consciousness.

Horror fiction, especially from indie voices like Jay Bower and Autumn Christian, brings this psychic fire into view. Bower’s Cadaverous is a gothic exploration of death’s intimacy. The protagonist’s encounter with the corpse world is less about fear than about becoming, transforming through the grotesque. Death is not an ending but a liminal threshold. The horror here isn’t meant to be escaped. It is to be experienced, absorbed, until it changes you.

Christian’s Girl Like A Bomb portrays horror as an erotic explosion. Her protagonist doesn’t run from destruction; she becomes it. Her body, her sexuality, and her psyche burst with existential chaos, creating something both monstrous and divine. The horror is internal and transformative. Like in depth psychotherapy, it is the loss of form that allows new psychic structures to emerge.

Even William James, a philosopher of religion, viewed horror as spiritual. In The Varieties of Religious Experience, he describes the “sick soul” who, through confronting despair, finds deeper meaning. He stated that the world is richer for having devils, as long as we always “keep a foot on his neck.” Horror, in this perspective, is not evil—it is essential. It is the very thing that, if endured, opens the soul to depth.

Whether in King’s tormented clairvoyants, Green’s mythic noir, Bower’s deathly intimacy, or Christian’s explosive sexuality, horror is never just fright. It is a psychic ordeal. Similarly, in my metaphysical horror novels—The Unholy, Goddess of the Wild Thing, and The Goddess of Everything—spiritual terror emerges from the cracks of family, religious betrayal, and dark feminine archetypes. In these stories, the sacred and the horrific intertwine. The desert landscape transforms into a dreamscape, and the protagonist must endure psychic dismemberment before reclaiming their soul. Here, horror is not an end; it is a sacred calling.

So then, whether in dreams, stories, or trauma, horror becomes a crucible. Jung called this nigredo, the blackening of the soul before rebirth. Eigen calls it the “storm and terror” of becoming. James names it the “dark night” before the mystical dawn.

In all these visions, horror is not something to escape. It is a sacred force to endure, a language of depth, and a strange kind of grace. When met with reverence, it does not destroy. It initiates.

Live Deeply . . . Read Daily!